Becoming a flying instructor can be one of the most rewarding careers in aviation. Being able to take a person with zero flying experience and tutor them through a training syllabus to help them realize their dream is an incredible feeling!

To become a flying instructor a pilot needs to have at least their Commercial Pilot Certificate & complete a Part 61 or Part 141 training program. Most students will complete the course in about 1-3 months with earnings for new instructors starting around $23-25 per hour.

There are many instructors out there and without them, most of us would not be learning to fly, but just how do you get to become a flying instructor? My time spent teaching was such a great experience and one day ill go back to it. In the meantime here is how you can step into that role and pass on your knowledge.

How Do You Become A Flying Instructor?

In the US, the FAA stipulates what flight experience and aeronautical knowledge a pilot must possess before they are even eligible to attempt a Certified Flying Instructor (CFI) Checkride or Flight Test.

To Be Eligible For The CFI Certificate a Pilot Must:-

According to: 14CFR§61.183 CFI Eligibility Requirements

- Be at least 18 years old

- Be the holder of a Commercial or Airline Transport Pilot Certificate with:

- An aircraft category and class rating that is appropriate to the flight instructor rating sought, and

- An Instrument Rating &/or appropriate privileges if they are to instruct on:

- An airplane category and single-engine class rating

- An airplane category and multiengine class rating

- A powered-lift rating

- An instrument rating

Then, there are two ways in which training for the CFI certificate can be approached:

- A Part 61 Training Path, or

- A Part 141 Training Program

Let’s look at both of these methods:

14CFR Part 61 CFI Training:

Under this Part of the FAA regulations, it allows for a very flexible training approach to becoming a flying instructor. It is more of a self-study route and is generally aimed at pilots who have vast amounts of experience and wish to become a CFI, or those pilots who already meet some of the requirements and just need to ‘Fill in the Gaps’ to then be ready for their written and flight examinations.

A student will only be ready to take the written and flight examinations once they have proved to, and been endorsed by a certified flight instructor.

To meet the Part 61 requirements, in addition to the above, must also:

- Receive and log ground training from an authorized flying instructor on the ‘Fundamentals of Instructing‘ to be able to pass a Written Knowledge Test based on:

- The Learning Process

- Elements of Effective Teaching

- Student Evaluation & Testing

- Course Development

- Lesson Planning

- Classroom Training Techniques

- Be able to demonstrate instructional proficiency in various areas, specific to the aircraft. This includes aircraft knowledge, maneuvers & Emergency procedures

- Receive and log a minimum of 15 hours of flight time

- Receive all applicable endorsements from an authorized instructor

- Pass a Written Knowledge Test on the areas to be taught to Private & Commercial pilot applicants

- Pass a Practical Flight Test – Known as a Checkride

14CFR Part 141 CFI Training:

This is a very structured program for becoming a CFI and will follow an FAA-approved flight and ground training syllabus. This is primarily what will be received at a flying school with an accredited program. Because the program follows the approved syllabus.

Based upon 14 CFR 141 Appendix F, the applicant for a CFI certificate must:

- Use an FAA-Approved Training Syllabus from an accredited flying school or company

- Complete an approved Flight Instructor ground school program of 40 hours

- Receive and log a minimum of 25 hours of dual instruction flight time

- Pass stage checks and an end-of-course flight test (Checkride)

This is how I and many other pilots got their CFI Certificates.

During my CFI training, I had to prepare lesson plans for teaching the entire Private & Commercial ground syllabus (I still have them now, the binder is 4″ thick and took me 3 months to write!).

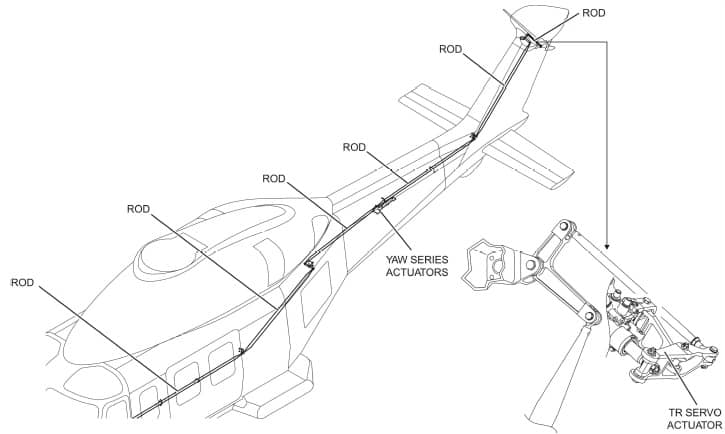

My flight training consisted of learning to fly in the left seat of the Robinson R22 helicopter which also meant learning to hold the Cyclic completely differently, because of the bent ‘T-Bar’ Cyclic in the Robinson series of helicopters.

Instead of resting your wrist on your right thigh, as you do in the right seat when holding the Cyclic, you now have to hold your wrist about mid-torso height so the student has their wrist resting on their thigh. It really takes some getting used to!

Not only that, but I also had to memorize and speak a set script for every maneuver so that I could tell the student what they should be doing on each control and at what time. Talk about reaching mental saturation!

I can tell you that this was by far the hardest part of all of my training! I hit a plateau and it took real effort and dedication to keep trying until I mastered it!

Join My Newsletter & Get Great Tips, Information and Experiences To Help You Become a Superb Pilot!

How Much Does It Cost To Become A Flying Instructor?

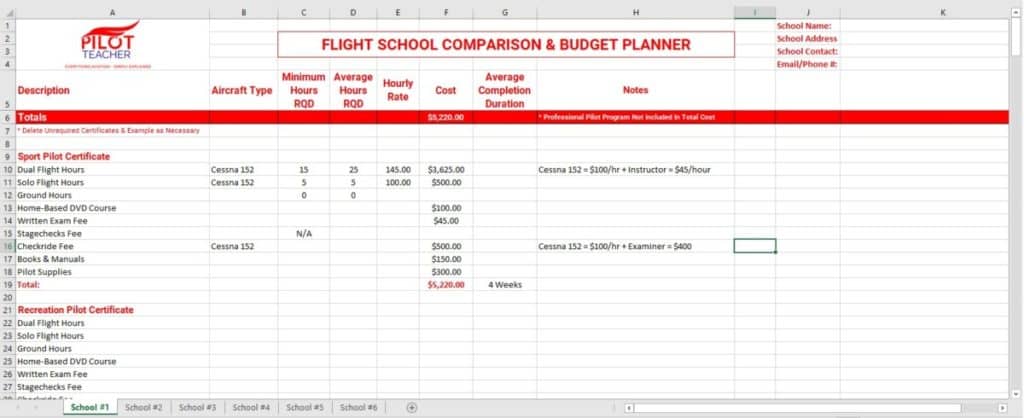

This data was researched and collected over the space of many weeks with over 30 flight schools contacted across the nation so I could bring you the most accurate and up-to-date average costs for the certificate you wish to pursue.

For a more detailed article comparing all the pilot certificate costs and the breakdowns, see the link at the end of this article!

Airplane

| Minimum Age: | 18 |

| Any Previous License Required: | Commercial or ATP |

| Total Flight Hours Required: | 25 |

| Dual Hours Required: | 25 |

| Solo Hours Required: | 0 |

| Ground Hours Required: | 40 |

Costs:

Flight Training:

The FAA requires the applicant for a Part 141 Certified Flight Instructor Certificate to have gained a Commercial FW Certificate or an Airline Transport Pilot Certificate FW before commencing CFI training.

Average Hourly Rate of Cessna 172 = $135/Hour

Average Hourly Rate of Flight Instructor = $45/Hour

FAA Minimum:

25 Total:

25 hours Dual Instruction x (135+$45) = $4,500

Total = $4,500

Student Average:

30 Total:

28 hours Dual Instruction x ($135+$45) = $5,040

2 hours Dual Flight Test Prep x ($135+$45) = $360

Total = $5,400

Ground School or Theory:

The Part 141 FW CFI training program requires 40 hours of Classroom-Based or One-On-One Ground Instruction to include:

- Fundamentals of Instruction (FOI)

- Aeronautical Knowledge

Average Ground Instructor Hourly Rate = $45/Hour

Examinations:

FOI Written Examination = Average $150 (Ranged from $125-$175)

CFI Written Examination = Average $150 (Ranged from $125-$175)

Flight Examination = Average $500 (Flight Examiner Ranged from $400-$600)

Extras:

Most students will require around $200 extras that can consist of:

- Books & Manuals

- Online Training Materials

Total Certified Flight Instructor – FW Costs:

FAA Minimum:

25 Hours Total:

- 25 hours Dual Instruction x ($135+$45) = $4,500

- 40 hours Dual Instructor Ground x $45 = $1,800

- FOI Written Examination = $150

- CFI Written Examination = $150

- Flight Examination = $500

- Extras = $200

Total = $5,500

Student Average:

30 hours Total:

- 28 hours Dual Instruction x ($135+$45) = $5,040

- 2 hours Dual Flight Test Prep x ($135+$45) = $360

- 40 hours Dual Instructor Ground x $45 = $1,800

- FOI Written Examination = $150

- CFI Written Examination = $150

- Flight Examination = $500

- Extras = $200

Total = $8,200

So these are just the costs to do the training for the CFI certificate. Don’t forget to add to these the costs of the Private, Commercial, Instrument, and any hour building to bridge the gaps. This will breakdown roughly as follows:

| Pilot Certificate | Minimum Cost | Average Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Private | $7,200 | $11,000 |

| Commercial & Instrument | $25,700 | $31,000 |

| CFI | $5,500 | $8,200 |

| TOTAL | $38,400 | $50,200 |

NOTE:

Most students will add additional ratings to their Flight Instructor Certificate to achieve greater levels of employability. The most common ratings are:

- Instrument Instructor – Certified Flight Instructor Instruments (CFII)

- Multi-Engine Instructor – Multi-Engine Instructor (MEI)

Helicopter

| Minimum Age: | 18 |

| Any Previous License Required: | Commercial or ATPL |

| Total Flight Hours Required: | 25 |

| Dual Hours Required: | 25 |

| Solo Hours Required: | 0 |

| Ground Hours Required: | 40 |

Costs:

Flight Training:

The FAA requires the applicant for a Part 141 Certified Flight Instructor Certificate to have gained a Commercial RW Certificate or an Airline Transport Pilot Certificate RW.

Average Hourly Rate of Robinson R22 = $300/Hour

Average Hourly Rate of Flight Instructor = $45/Hour

FAA Minimum:

25 Total:

25 hours Dual Instruction x ($300+$45) = $8,625

Total = $8,625

Student Average:

30 Total:

28 hours Dual Instruction x ($300+$45) = $9,660

2 hours Dual Flight Test Prep x ($300+$45) = $690

Total = $10,350

Ground School or Theory:

The Part 141 RW CFI training program requires 40 hours of Classroom-Based or One-On-One Ground Instruction to include:

- Fundamentals of Instruction (FOI)

- Aeronautical Knowledge

Average Ground Instructor Hourly Rate = $45/Hour

Examinations:

FOI Written Examination = Average $150 (Ranged from $125-$175)

CFI Written Examination = Average $150 (Ranged from $125-$175)

Flight Examination = Average $950 (Flight Examiner Ranged from $400-$600)

Extras:

Most students will require around $200 extras that can consist of:

- Books & Manuals

- Online Training Materials

Total Certified Flight Instructor – RW Costs:

FAA Minimum:

25 Hours Total:

- 25 hours Dual Instruction x ($300+$45) = $8,625

- 40 hours Dual Instructor Ground x $45 = $1,800

- FOI Written Examination = $150

- CFI Written Examination = $150

- Flight Examination = $500

- Extras = $200

Total = $11,425

Student Average:

30 hours Total:

- 28 hours Dual Instruction x ($300+$45) = $9,660

- 2 hours Dual Flight Test Prep x ($300+$45) = $690

- 40 hours Dual Instructor Ground x $45 = $1,800

- FOI Written Examination = $150

- CFI Written Examination = $150

- Flight Examination = $500

- Extras = $200

Total = $13,150

Just like the fixed-wing costs, these are just the costs to do the training for the CFI certificate. Don’t forget to add to these the costs of the Private, Commercial, and any hour building to bridge the gaps. This will breakdown roughly as follows:

| Pilot Certificate | Minimum Cost | Average Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Private | $15,300 | $22,600 |

| Commercial | $12,800 | $19,600 |

| CFI | $11,400 | $13,200 |

| TOTAL | $39,500 | $55,400 |

NOTE:

Most students will do their Instrument Rating during the hour-building phase of their Commercial Certificate. Then once they have received their Flight Instructor Certificate, take another exam to become a Certified Flight Instructor Instruments (CFII). This can dramatically increase a pilot’s employability.

This was also the route that I took.

How Long Does It Take To Become A Flying Instructor?

Once you reach the point to begin your CFI training, the training program you undertake can vary a lot. Some schools have a very structured approach while others are a bit more relaxed.

To give you some indication, if you had a flight lesson in the morning and a ground school session in the afternoon you would be looking at around a month of full-time training if you were following a Part 141 program.

This will be a serious undertaking at that pace. I have found that most students take anywhere from 2-3 months to get all the flight training, ground training, 2 written exams, flight test, and lesson plans completed.

As I mentioned, this was by far the hardest part of my training because of the talking while flying part. Some schools may have very different programs, but I know that the school I was part of had every instructor using the same verbal maneuver script.

This made it very easy for students to swap back and forth between instructors if they wanted a really accelerated training program and needed multiple instructors. This is where consistency really helps the student develop quickly

For me, my CFI training took about 3 months from the first lesson to passing my Checkride.

How Much Do Flying Instructors Get Paid?

At the time of writing this article in 2023, most job advertisements for flight instructors were offering the following remuneration ranges:

Airplane

Most schools were looking for Instructors with CFII (Certified Flight Instructor Instrument) & MEI (Multi-Engine Instructor) ratings. I only found one advertisement for just a CFI and this was paying at the bottom end of the pay scale.

Remunerations were anywhere from:-

For new instructors with low flight hours, you will be looking at the lower end of the scales

- $20 – $50 per flight/ground hour

or - $25,000 – $75,000 per year salary

Helicopter

Most schools were also looking for Instructors with CFII (Certified Flight Instructor Instrument):

Remunerations were anywhere from:

- $23 – $40 per flight/ground hour

or - $25,000 – $150,000 per year salary

All salaries are based on many variables:

- Experience

- Size of school

- Training students or company pilots

- Large companies or government agencies

When starting out as a flight instructor be prepared to be working for very little compensation! Most training schools know that instructors are looking to get their first flying job and they take advantage of that!

Unless you are finishing your flying career with thousands of hours and then become an instructor, you will not be doing this job for the money that is for sure!

Once you have some good experience and get on with a good company or school, you could then have a good salary, but until then be prepared to keep eating the same way you did as a student!

A Typical Flying Instructors Earnings:

My instructing days were split up into two-hour blocks and I did four blocks each day, Monday to Friday.

A typical day would maybe be 3 flights of around 1.5 hours each and a 2 hour block of ground school:

- 3x 1.5 hour Flights @ $25per hour = $112.50

- 1x 2.0 hour Ground @ $25per hour = $50.00

- Daily Earnings = $162.50

- 5 days per week = $812.50

- $3250.00 Per Month or $39,000 Per Year

What Are The Job Prospects For Flying Instructors?

Job prospects for low time flying instructors are always in demand at large flight schools as they are always sending on the majority of their current instructors once they start to reach around 1000 hours. The main reason they do this is to entice students to their school by offering them job prospects when they finish training.

Of course, not all students get hired at the school at which they trained, but for those who are prepared to move to get their first flying job, there are plenty of opportunities out there!

Taking a look over the aviation job posting websites shows that there are always positions available. You may just need a bit of luck to secure a job in the town of your choice, or it may require you to gain some experience before being able to move back to your location of choice. If you are not picky, then you should have no problem finding that first flying/instructing job!

To Finish

Teaching someone how to fly is a very satisfying experience and although you can be a brand new pilot yourself, having a humbled view that you are only teaching to operate an aircraft within its limitations and the rules set forth by the FAA, will keep you and the student safe.

A low-time flying instructor still does not know how to fly, but taking things slowly, not pushing limits, and enjoying what you are teaching will ensure both you and your students will look back on this time and have great memories.

Instructing was one of my greatest life achievements and one day I will get back into helping people realize their dreams of taking flight!

Further Reading

If you found this article helpful and would like some more to read I highly recommend you take a look at my other articles listed below:

- Cost To Become a Pilot: All the Licenses Compared!

- Starting Flight School? Essential Gear For Every Student

- Which U.S. Flight Training Visa? Your Easy, Helpful Guide!

- Helicopter Pilot Careers: 20 Jobs a Pilot Can Do?

- Skills Needed To Become a Pilot? – A Flight Instructors Perspective

To help you keep track of all your finding on your next flight school I created the free Excel Planner. With information for up to 6 flight schools it will give you an instant side-by-side comparison as you input the data.