Helicopters are a truly remarkable piece of engineering and how they are able to land in almost any location is incredible. Many people always ask me why they saw a helicopter landing a certain way and why it seemed different to the usual way a helicopter lands. There are in fact many ways that a helicopter can make an approach to a landing site, and also several ways in which it can touch down, both with its engine/s running and without!

A helicopter can make shallow, regular, and steep approaches to a landing spot depending on the type of obstacles on the approach path and then touch down to the ground using a hover landing, no hover landing, vertical descent, or running landing. The pilot selects each for every landing location.

I too was under the impression that all helicopters landed the same way until I became a helicopter pilot and soon learned there are a whole plethora of landing techniques used to get the helicopter safely on the ground. I use all of the techniques as required in my day job piloting a utility helicopter, so if you wish to know more about the techniques I use please read on.

Are There Different Types of Helicopter Landing Approaches?

Helicopters are able to land in so many locations not available to any other aircraft, because of this each landing spot is completely different and requires a little bit of planning to ensure the helicopter can make it into the spot safely. As I write this I’m sat on a road in a forest logging area that has just been consumed by a wildfire.

The road is dusty which makes visibility poor when my rotor wash hits the road, there are logs and stumps lying all over the place. To also make it more challenging the forestry company has to leave random trees to allow for birds to use which creates hazards that can be hard to see during the approach.

To land at this location I opted to pick a steep approach with a no hover landing (more on these later). Now, if I go to pick up the forestry workers that are located down in a hole within the forest, that requires a completely different approach into the landing spot, again all decided during my overhead recce of the spot before commencing the approach.

Because there are so many ways a helicopter needs to get into a landing spot, there need to be many ways in which to safely fly the aircraft into them. Here are some of the most common approach techniques used by helicopter pilots all over the world:

Normal Approach

This is by far the most common approach helicopter pilots train for and use in normal flying tasks. The approach is used into a landing spot that is in the open and has very minimal obstacles around it. The pilot will set up the approach with roughly a 20°- 30° descent angle and what appears to be a walking pace over the ground when at height.

As the helicopter descends down this imaginary approach path the pilot is slowly reducing airspeed to maintain this walking pace over the ground. As the aircraft gets closer to the ground its speed over the ground will appear to get faster if the same airspeed is maintained. By maintaining a walking pace over the ground, the helicopter is constantly slowing down as it descends.

If the pilot has executed the technique correctly the helicopter will arrive at a 5-10ft hover over the landing site with zero airspeed. This is a typical or normal approach for a helicopter when landing at an airport or dedicated helipad.

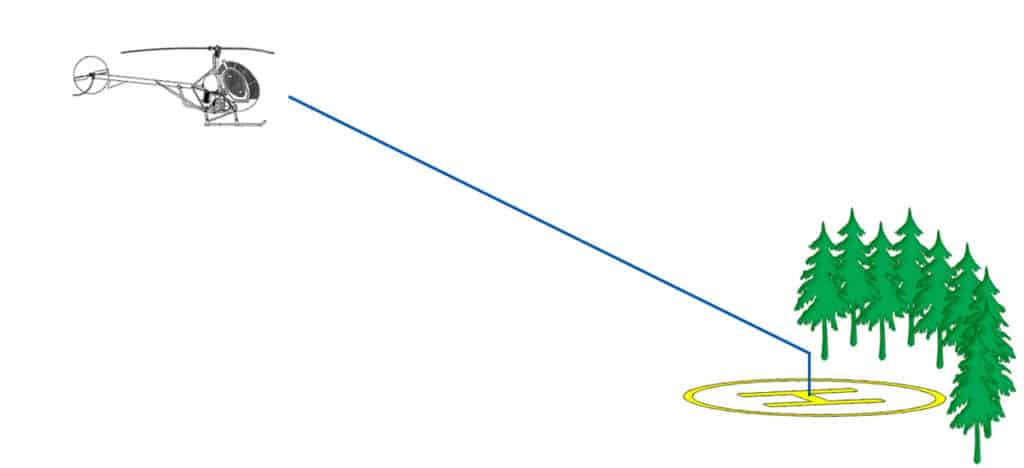

Steep Approach

The steep approach is used when there are obstacles on the approach path to the landing spot. Buildings, trees, powerlines, towers, livestock, and hillsides are some of the most common things that need to be flown over at a higher altitude before making it into that landing spot. Because of these obstacles, a higher descent angle is required to ensure the helicopter does not hit them on the approach in.

The steep approach can be any angle from a regular approach up to around 70°. The steepness of the approach will be dictated by the height of the obstacles on the approach path. The taller the obstacles, the steeper the approach needs to be. Just like a regular approach, the pilot sets up the helicopter at a walking pace over the ground, but then the walking speed will become much slower as the helicopter begins to descend because the helicopter needs to descend more than it moves forward.

The pilot will draw an imaginary line to the landing spot in their mind and then fly the helicopter down that line, adjusting as they go to compensate for wind. As the helicopter approaches each obstacle the pilot will be looking all around to ensure the tail rotor and main rotors are clearing the obstacles by a healthy distance as the helicopter continues its approach.

The pilot will then fly the helicopter either to a 5-10ft hover to assess the landing location for the best place to set the helicopter down (for example, an unprepared landing spot of the edge of a swamp or in a clearing) or fly it all the way to the ground to a prepared helipad.

The steep approach is used primarily when operating out in the wilderness to unprepared landing spots, like the logging road I’m sitting on right now.

Join My Newsletter & Get Great Tips, Information and Experiences To Help You Become a Superb Pilot!

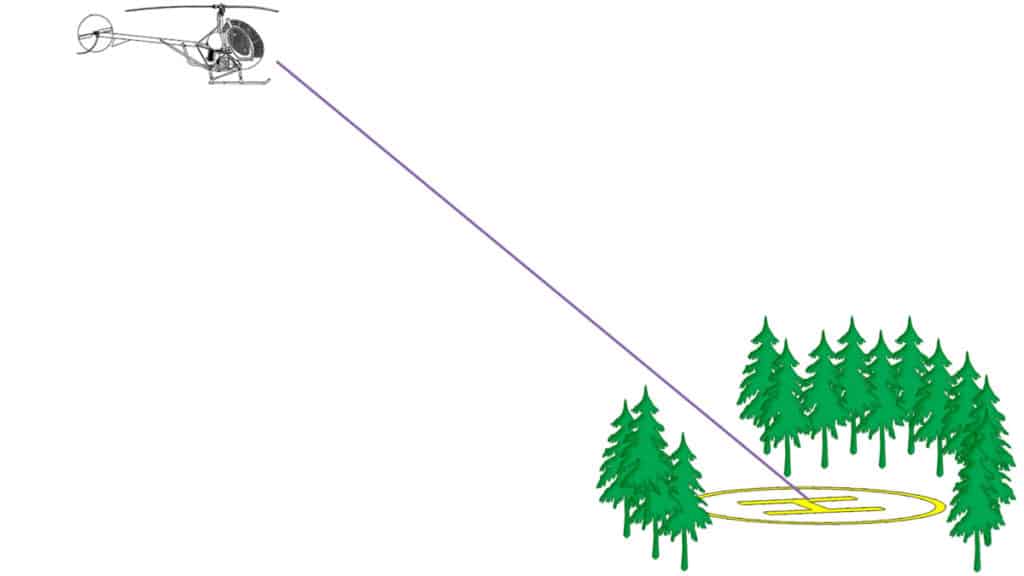

Confined Area Approach

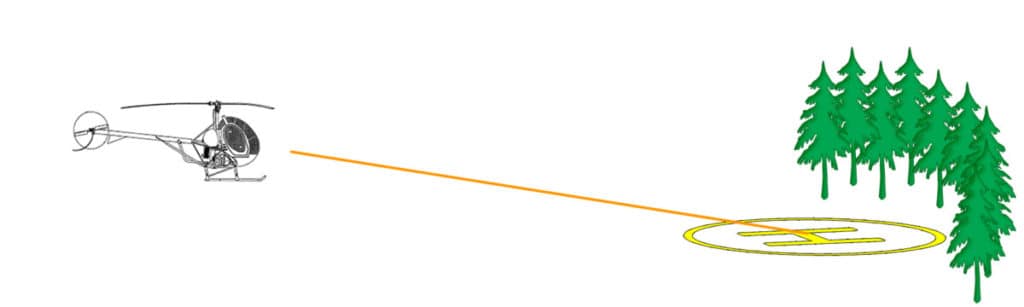

A confined area approach is used when the landing spot is in a very tight location and usually consists of a two-stage approach. For example, a MedEvac helicopter landing at a crossroads in the middle of a city, or a helicopter descending into trees to pick up crews. If you are old enough to remember Airwolf, its lair was in a mountain where the helicopter had to descend vertically inside. This is a confined area.

Depending on the type of terrain and obstacles around the landing spot the helicopter will make a normal or steep approach to the top of the confined area, then descend vertically down onto the landing spot. This is why it is sometimes referred to as a two-stage approach.

This photo above was when I had to land in a clearing within 50ft tall trees to take water samples as part of an environmental survey of the groundwater surrounding a coal mine. Most of the landing spots were like this and because the treetops were all of a similar height, a normal approach to the top of the trees was performed before descending down into the hole.

Because I had not landed at these sites before, I brought the helicopter to a hover above the trees but adjacent to the ‘Hole’. Then I could look down into the clearing and see what obstacles would face me on the way down and where I needed to park the helicopter once at the bottom.

Once I was happy, I could then move over the hole and descend down. From that point on I was able to complete a normal approach to the opening and then descend straight down. The first time always requires a visual recce before committing.

Confined area approaches can be some of the most challenging to execute because of the number of obstacles and the limited amount of vision the pilot has of the area below the helicopter. A few passengers or crew members in the helicopter really help get more eyeballs looking around for potential hazards that could present a problem to the helicopter. By having open communication, the pilot is able to make safe descents providing the hole is big enough to fit the helicopter!

Shallow Approach

Shallow approaches are used by many pilots when flying in the mountains as it uses less power to arrest the helicopter’s rate of descent at the bottom of the approach. When a helicopter gets higher in altitude, the amount of air molecules in the atmosphere reduces due to the reduction in air pressure with altitude.

The reduction of air molecules provides fewer molecules for the rotor blades to work on and produce lift and the engine to mix with fuel and burn. Because of this, power from the helicopter engine and lift reduces with altitude, and that power/lift is required by the pilot to slow the helicopter’s descent, especially if coming in steep and ‘Hot’.

For this reason, when a helicopter approach is flown shallow in the mountains, the power required for the approach stays pretty much the same all the way to the landing spot on the mountainside. If the pilot is able to begin the approach and is not running out of power or lift then a safe, stable approach should be able to be made all the way to the landing spot. If at any time the approach becomes unsafe the pilot can dive the helicopter away from the mountain and reject the landing.

If a steep or normal approach is made and the pilot then beings to pull in power just before landing it may not be available. This results in the descent of the helicopter not being reduced and a hard landing, or worse ensues.

The second time a shallow approach is used is during emergencies when the helicopter has to make a running landing. A running landing is discussed in the next chapter but a shallow approach allows the aircraft to be using minimal power on approach and allows the pilot to get the aircraft low to the ground and gradually slow it down so that if anything bad were to happen the helicopter can be quickly placed onto the ground with as soft a touch down as possible.

Weather-Cocked Approach

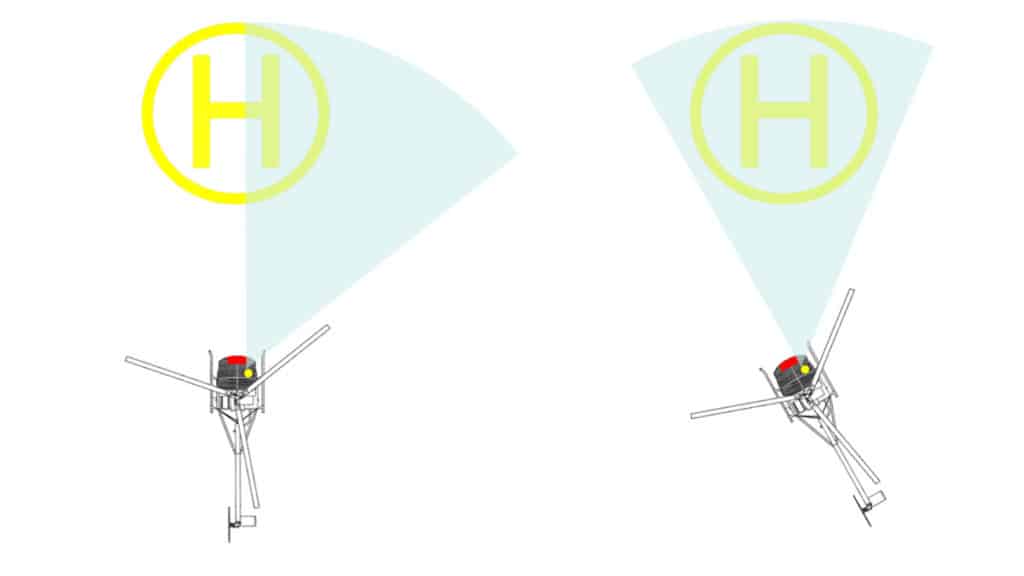

The weather-cocked approach is very common and you will see helicopter pilots doing this using any of the above approach profiles. As a helicopter slows down its nose begins to rise upwards. As this happens, the instrument panel begins to block the view of the landing spot. To overcome this blockage pilots will point the nose of the helicopter to the left and fly the approach at an angle so they can put the landing spot in view to the right of the instrument panel.

By doing this the entire approach path and landing spot remain in view to aid the pilot in flying the helicopter down the set approach path and keeping an eye out for obstacles at all times while on the descent. If the pilot is good they will orientate the helicopter so it is pointing into the wind but will be flying over the ground at an angle so they can see.

Are There Different Types of Helicopter Landings?

Once a helicopter has completed its approach to the selected landing spot it can touch down using 3 techniques. Hover then land, a no-hover landing or a running landing are the most common. Each touchdown technique will be selected by the pilot to meet performance or situational circumstances.

Hover & Land

This is by far the most common touch-down technique used by helicopter pilots. The helicopter is slowed during the approach to enter into a stable hover over or next to the landing spot and between 5-10ft high. This technique allows the pilot to inspect the landing spot to ensure it is free from obstacles that could puncture the belly of the helicopter and asses for sloping ground.

By coming to a hover it gives the pilot time to select the exact spot the helicopter needs to be over before committing to setting the aircraft down. This is especially important when landing in unprepared areas like the bush.

The Astar that I fly has a very low tail rotor so I use this technique lots to ensure my tail rotor will be in a clear area away from small samplings, tall grass, bushes, or rising ground. The mirrors by my feet help me to see the rear and underside of the helicopter to pick the perfect touch-down spot.

No Hover Landings

No hover landings are just as they sound. The helicopter is slowed during the approach but instead of terminating to a hover and then setting down, the approach is flown all the way to the ground in one smooth motion. This technique is mainly used when power is limited or when the helicopter is operating in areas of dust and snow.

Helicopters use the most power when in a hover. The power being produced by the engine/s also reduces as air temperature increases, humidity increases or the helicopter is landing at a high altitude. If the pilot tries to hover and there is not enough power available to the helicopter it can land hard.

To overcome this, the pilot picks the landing spot and flies the helicopter all the way to the spot with no pause for hovering. The pilot has to be careful and still monitor their power and approach speed to ensure this type of landing is completed safely, but it is a way to land the helicopter using minimal power. This technique is used lots when landing in the snow on mountains, like heliskiing for example.

Another reason a no hover landing would be completed is when a helicopter with skids (No Wheels) is landing in a dusty or snowy environment. As the helicopter slows and gets close to the ground at the end of the approach, the rotor wash will stir up dust and snow to create a snowball/duststorm that can completely reduce the pilots’ visibility. This is when a lot of accidents happen.

To help minimize this reduced visibility the pilots reduce the amount of time spent in the reducing visibility by picking an object right next to the landing spot and flying a no hover landing right to that object. By doing this, the snowball/dustball stays behind the helicopter for as long as possible, and then the pilot has a close visual reference to stay focused on just as the dust/snow begins to reduce visibility.

Running Landing

Running landings are mainly used in normal everyday operations for helicopters equipped with wheels. It is the larger helicopters that are usually equipped with wheels and because of their size, they create a lot of rotor wash! This rotor wash picks up sand and debris and hurls it at great speed. Not good for other aircraft parked nearby!

I used to fly this approach all the time in the ambulance when landing at the airport. It is a normal approach and then touch the wheels down with about 20kts of airspeed. Once set down the helicopter can then ground taxi to their parking spot using far less power, thus creating far less rotor wash that stirs up the debris.

The second reason is just like the no hover landing and it’s to help keep the dustball behind the helicopter when landing on a dirt airstrip or somewhere similar. Keeping a little forward airspeed when landing allows the dirt to stay behind the cockpit allowing the pilot/s to see. Of course, this technique can only be used to runways or large open areas where there is lots of room for the helicopter to ‘Run-On’.

For helicopters with skids, a running landing is mainly used when dealing with an emergency situation. Failures like the loss of flight control hydraulics make moving the flight controls very heavy and trying to hover a helicopter without hydraulics (If it’s supposed to have hydraulics) is going to end up in a crash.

A small amount of forward speed helps to keep the helicopter more controllable and running on the helicopter greatly improves the chances of a successful emergency landing. There are lots more emergency situations where running on is favorable but you get the idea.

How Does A Helicopter Land When The Engine Stops?

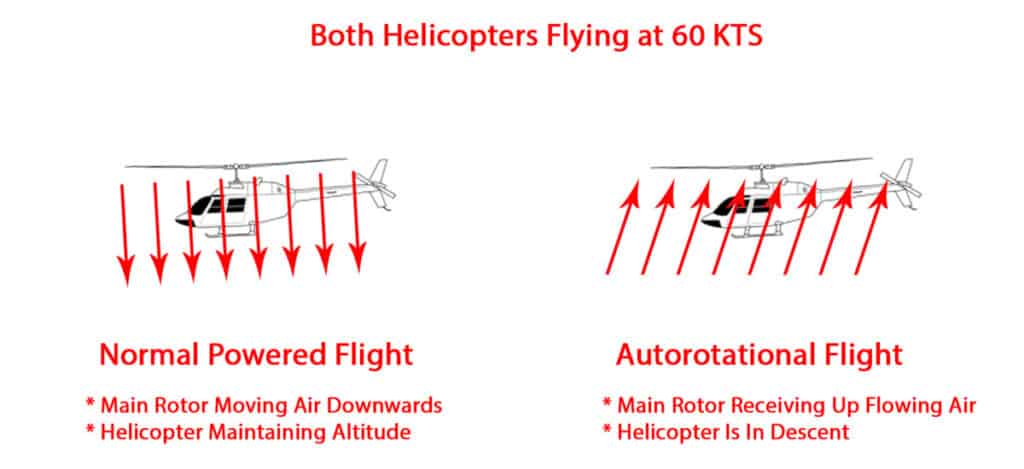

In normal flight, the engine/s produce power which is fed into the main transmission which turns both the main rotor and the tail rotor systems. When the engine/s stop producing power in a helicopter the rotor systems must then find an alternate method to be powered. To find this alternate method the pilot puts the helicopter into an Autorotation.

As a helicopter enters an autorotation it begins to descend. The up-flowing air from the descent keeps the main rotor system turning and storing energy. Just before landing, the pilot will use this energy to arrest the rate of descent while slowing the helicopter to make a smooth landing.

What is an Autorotation?

During pilot training, every pilot must learn and be able to successfully complete a landing without the helicopter engine being used to power it. Practicing this flight maneuver is probably one of the most practiced maneuvers in the pilots’ complete training syllabus – and rightly so, it’s the one maneuver that will save their life if the engine were to ever stop.

The flight maneuver is called an Autorotation and its name says it all! It is a way to automatically keep the main rotor system rotating should the engine be unable to do so.

When in normal flight, the helicopter engine is turning the main rotor system. To fly and maneuver the helicopter each main rotor blade varies its pitch angle as it rotates around the main rotor mast. The pitch on each blade creates drag as it rotates through the air.

The more pitch that the pilot places on each rotor blade, the more drag it creates, and the more power is required from the engine to overcome this drag and maintain the entire rotor system RPM within set limits.

When a helicopter engine stops, the power overcoming this drag is gone so the first thing the pilot has to do to prevent the drag from reducing the RPM of the main rotor system is to remove it. They do this by lowering the collective control, which reduces the pitch on all of the main rotor blades.

If the pilot does not do this within the first second or two following a loss of power the main rotor RPM will decay and the helicopter will become unrecoverable leading to a fatal descent of the aircraft. As the pilot is reducing the collective they will also be altering the airspeed of the helicopter to around 60-70knots to put the helicopter into the configuration for autorotation.

Once the helicopter is established in autorotation (blade pitch is flat and airspeed is set) the next part of the maneuver will become the next important step as the helicopter descends – Upward Airflow

What is Helicopter Upward Airflow?

As a helicopter descends without its engine power the airflow meeting the rotor system is coming upwards from below. The up-flowing air is what keeps the main rotor system turning like a windmill and storing energy ready for the pilot to use to arrest the rate of descent at the bottom of the autorotation.

The main rotor system has now changed from being the wing that keeps the helicopter airborne to now being a wing that is storing energy during the helicopter’s descent. The up-flowing air is enough to maintain the RPM of the main rotor system providing the pilot monitors the RPM gauge and adjusts the collective control to keep the main rotor RPM in the green band.

By keeping the main rotor rpm in the green the energy from being turned by the airflow is being stored ready for the landing.

How Do Helicopters Land After an Autorotation?

The helicopter is in its autorotational descent, the main rotor system is storing energy and the helicopter is flying forward at 60-70 kts. As the ground approaches and at around 50 feet the pilot will begin to flare the helicopter using the cyclic control to reduce its forward airspeed.

As the helicopter’s airspeed begins to decay it will want to drop out of the air. At this point, the pilot levels the helicopter and waits until the helicopter is roughly 5-10ft above the ground (larger helicopters start the flare and level at higher altitudes). At this point, the pilot will raise the collective control all the way in a smooth motion to use that stored energy to provide a last moment of lift to cushion the touchdown.

If the pilot has done the maneuver correctly the helicopter will touch down smoothly with very minimal forward speed.

What Are Helicopter Elephant Foot Prints?

Having the engine fail on a helicopter is not really a big problem if the pilot is flying over an airport or large flat open space, but what happens if they are over a city or forest. Well, this is where a bit of luck comes in! There are certain times when a helicopter will only be able to land dead ahead and that is on takeoff or late on an approach. If there are obstacles in the way then that’s just bad luck.

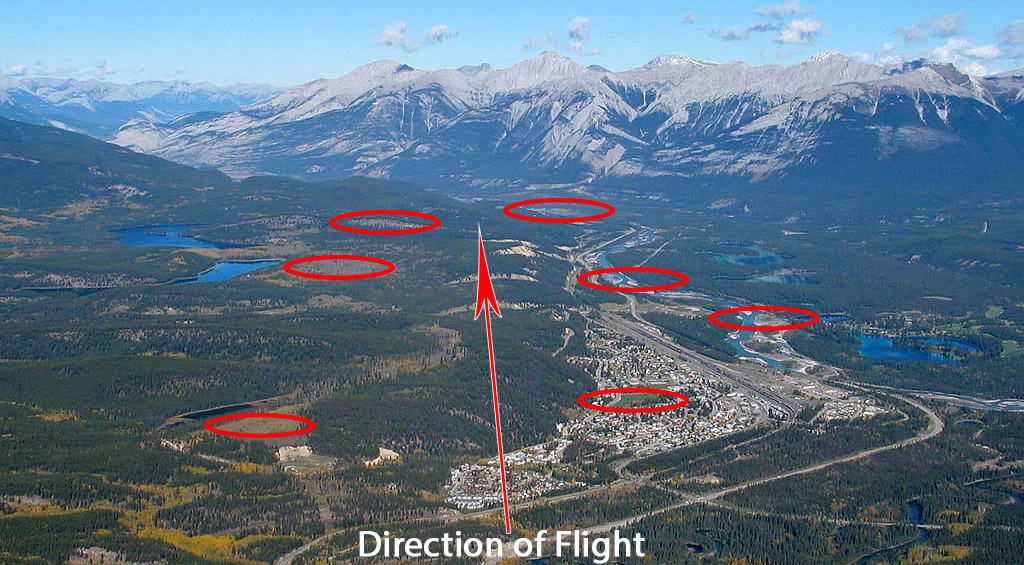

As pilots, we are always trying to fly in and out using the path with as few obstacles as we can, but sometimes there is no way of flying without them in our path. When in cruise flight it is a little different as this is where we look for Elephants Footprints.

When elephants walk they make big holes on the ground – it is this same thing we look for as we fly – Big holes to land in as we cruise along. The higher the helicopter the more holes become reachable to glide into.

This is a trick that is taught in flight school and when flying along the pilot should always be looking for the next emergency landing spot. With time, the pilot does this without even realizing it and if they are good they will remember the ones they have just flown over in case they need to turn around to get the helicopter into the wind for the autorotation.

The fewer places there are to land, the higher the helicopter should be to allow the pilot time to get that helicopter into that one emergency landing spot. Height and airspeed are your friends in a helicopter but sometimes there are no clear, open areas available, and that just bad luck if the donkey stops working!

Further Reading

If you found this article helpful may I suggest a few more for you: